| RENTS ARE COOLING, BUT NOT EVERYWHERE |

In a recent report, America’s Rental Housing 2024, we noted that rental markets are finally cooling after substantial overheating. This slowdown in rent growth has only continued. In the fourth quarter of 2023, asking rents increased by just 0.2 percent year over year in the professionally managed apartment market, a dramatic turnaround from the 15.3 percent rise in early 2022. Whether this recent cooling will be a boon to affordability remains an open question. To date, slowing rents and even modest declines in some markets do not appear to be enough to offset the pandemic’s historically high rent increases.

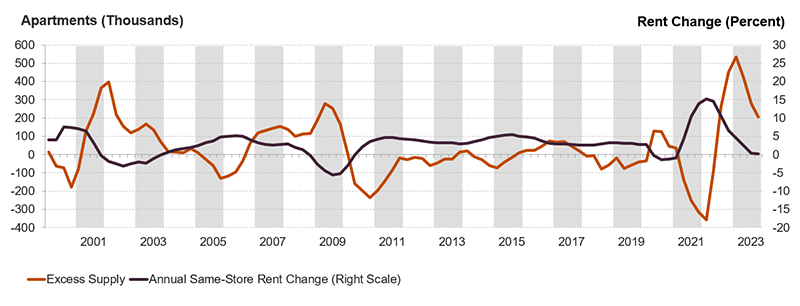

Rent growth in recent months has cooled thanks to an influx of new supply that is outpacing demand, mirroring a longer-term trend. Over the last two decades, the largest drops and decelerations in rents occurred when annual apartment completions were well above net household formations (Figure 1). According to RealPage data, about 439,000 apartments came online on an annualized basis in the fourth quarter of 2023 while the number of households rose by just 234,000. This excess supply pushed the vacancy rate up to 5.8 percent, the highest in more than 10 years.

Figure 1: Excess Supply Has Helped Slow Rent Increases

Notes: Excess supply is the difference between annual supply and demand. Data cover professionally managed apartments in buildings with at least 5 units.

Source: JCHS tabulations of RealPage data.

While supply additions are largely at the high end of the market, the sheer influx of new apartments does seem to be slowing rents and raising vacancy rates across property classes. In the fourth quarter of last year, rents grew by just 0.7 percent for the highest-quality Class A apartments, which tend to attract higher-income renters, a steep deceleration from the 7 percent rise the previous year (Figure 2). Interestingly, though, vacancy rates increased the fastest among the mid- and lowest-quality apartments, with asking rents falling slightly in both the Class B and Class C market segments. This may be evidence of filtering. As higher-quality apartments came online, it provided opportunities for households to upgrade, freeing up lower-quality apartments—where demand tends to run closer to available supply—in the process. Whether filtering has extended beyond the professionally managed apartment sector is unknown.

Figure 2: Rents Are Cooling and Vacancy Rates Are Rising, Even for Lower-Quality Apartments

Notes: Data cover professionally managed apartments in buildings with at least 5 units.

Source: RealPage data.

Rent growth is also moderating across a wider range of markets than in previous years. At the end of 2023, nominal asking rents fell by an average of about 2 percent in 59 of the 150 markets tracked by RealPage. However, rents remain high, as this modest decrease came after significant rent increases in 2022. For example, rents dropped by more than 5 percent in five markets (Austin, Boise City, Cape Coral-Fort Myers, North Port-Sarasota, and Jacksonville), following year-over-year increases of more than 20 percent in the first quarter of 2022 when national rent growth peaked.

While rents fell in some places, increases were still the norm, albeit at a slower rate of growth. The 91 markets where rent was still rising at the end of 2023 posted an average growth rate of about 3 percent, and just eight markets grew by at least 5 percent year over year (Figure 3). This was a swift turnaround from the first quarter of 2022 when rents rose in every market by an average of 14 percent. At the peak, rents increased by more than 5 percent in all but four markets and by more than 20 percent in 25 markets.

Figure 3: Rent Growth Moderated in the Last Quarter of 2023, a Significant Turnaround From the Peak in 2022

Notes: Rent growth is for same-store asking rents. Data cover professionally managed apartments in buildings with at least 5 units.

Source: JCHS tabulations of RealPage data.

While the excess supply has the potential to improve affordability conditions, there are limits to this process. Though rising at a slower pace, rents have continued to grow in many markets and remain well above pre-pandemic levels. Against this backdrop, the new supply is unlikely to reverse the significant rise in cost-burdened households that hit a new record high in 2022. Since the last quarter of 2019, average asking rents have risen by about $400 (or about $125 in inflation-adjusted terms). Nominal rents fell in just 2 markets over this longer period, suggesting that recent market cooling is unlikely to make enough of a dent in cost burdens to return the country to pre-pandemic levels. Still, nominal rent cuts in 34 markets may help bring cost burdens down from their all-time high.

Ultimately, new supply and stabilizing demand have likely provided slight improvements in affordability conditions from the worst on record. However, the progress may be short-lived. The professionally managed apartment sector is showing a pickup in demand, and multifamily starts have slowed as high interest rates and softening markets reduce the appeal of the apartment sector to investors. The record-high number of multifamily units under construction should help supply in the next year, but slowing starts amid currently rising demand could create further challenges down the road. Especially in this environment, federal, state, and local governments should not count on new supply alone to solve the affordability crisis.